The new age of on-demand transit in Canada

Dr. Willem Klumpenhouwer

Postdoctoral Fellow, Transit Analytics Lab, University of Toronto

Smartphones have enabled a wide range of mobility options for Canadians. You can rent a scooter or a bike, hail an Uber or a Lyft, or reserve a car share, all with a few taps. These services are possible because of the explosion of “the cloud”, a tech-sector term for using someone else’s computing space, allowing businesses to focus on their own priorities while leaving the computational power to specialized companies.

In 2018, 88 per cent of Canadians reported having a smartphone, and a 2020 figure estimates that 90 per cent of businesses run their service in the cloud. Put smartphones and cloud computing together, and you have the ingredients to create new mobility technologies that were otherwise impossible.

These innovations are making their way into the transit realm. Dozens of Canadian municipalities have turned to new on-demand transit technology companies, many of whom are headquartered in Canada, offering a new, more personalized form of transit. Supported by Mitacs* funding, OSPE partnered with the University of Toronto’s Transit Analytics Lab to co-supervise a research project which surveyed 14 on-demand transit systems and vendors that have appeared across the country since 2015. Many of these projects introduced transit into towns and cities that previously had none.

The premise of on-demand transit is simple: In times and areas with lower demand for transit, we can serve stops more efficiently if we go directly to where and when people are waiting, instead of following a pre-planned route and schedule. Traditionally, this type of service has been done by phone, where you would quite literally “dial a bus” and make a request for a trip, often hours or even days in advance. Now, requests are made through an app on your smartphone, and handled almost instantaneously.

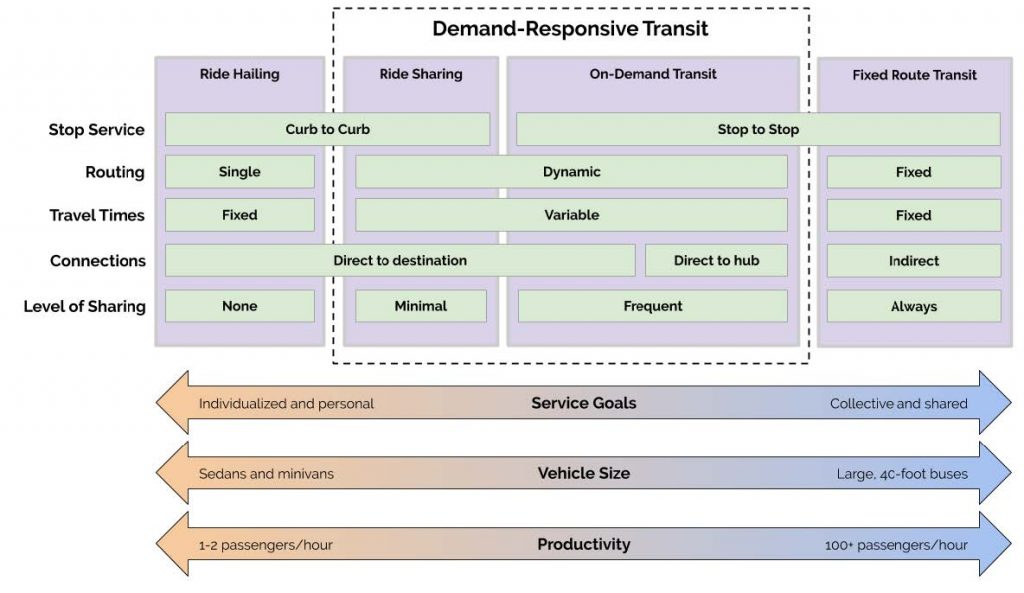

In reality, there is a whole array of service types and configurations for demand responsive transit services, as outlined in Figure 1. Small vehicles that pool trips together but still provide curb to curb service (often referred to as ride sharing) offer more personalized service at a higher cost and lower efficiency. At the other end of the spectrum is on-demand transit that looks more like traditional fixed route transit, moving larger amounts of people in larger buses, but less directly.

These applications are also able to provide transit agencies with a lot of feedback and flexibility in service planning. Agencies can get instantaneous reports about their service use and quality, both by measuring trip lengths and wait times and through a rating system that allows the customer to provide feedback on individual trips.

There is also adjustable service. Setting the vehicle capacity and maximum trip length will force the algorithms running thousands of routing options in the cloud to look for solutions that don’t keep passengers on board for too long and guarantee a seat once a trip is reserved.

This feedback loop has become especially useful during the COVID-19 pandemic. The advantage of modern demand-responsive transit (DRT) systems is that they are both flexible to demand and can dynamically adjust the capacity of vehicles. This has allowed agencies to adapt more cost-effectively to the decrease in transit demand brought about by the pandemic and remove a lot of the uncertainty surrounding crowding and capacity enforcement from the day-to-day operations.

By adjusting vehicle capacities, passengers have certainty that they will have physically distanced room on the bus when it arrives, and drivers will not have to enforce physical distancing by refusing pickups. A few agencies used the pandemic as an opportunity to test the flexibility of the service, both in scalability and adaptability. Belleville, Ontario which operated evening DRT service before the pandemic, made the decision to transition to exclusively DRT service for several months during the initial outbreak. As they were using existing full-size buses as part of their service, transitioning involved minimal infrastructure costs and driver training. Now that ridership has started to return, they have made the switch back to fixed route service but have kept their on-demand evening service.

In Alberta, Okotoks reported utilizing the extra vehicle hours made available by lower demand to provide a grocery delivery service, minimizing the increase in operating costs. Agencies such as Okotoks, with smaller vehicles, may have a harder time providing the appropriate level of physical distancing, even after limiting capacity through the booking process.

Regardless of the pandemic, while technology has expanded the situations in which on-demand service is feasible, it is not a one-size- fits-all solution. Traditional fixed route service in dense areas still carries vastly higher numbers of passengers, and it remains to be seen just how much these new on-demand transit technologies can scale with growing demand. On-demand transit is still best suited for low-demand areas and times where the goal is to provide coverage to many stops at a lower cost.

It’s also not clear how much the “digital divide” has limited access to the benefits offered by these new systems. While most services offer a call-in option to book trips, it is usually only during business hours, requiring late-night travellers to plan ahead. Agencies reported few to no issues with the use of these applications, but there is more work to be done to understand who this new service may be leaving behind.

On-demand transit has seen a recent renaissance, both in Canada and around the world. Service that wasn’t possible before is now successful, enabling much-needed transit in rural and suburban areas. As we learn about what Canadian transit agencies are doing, the next step is to better quantify the value and limitations of this new approach to demand-responsive transit.

Transit systems and developers alike can learn from these early adopters of technology-driven service. More on-demand transit services are expected to appear in Canadian cities in the next two years, powered by Canadian technology companies. Engineers will continue to play a vital role in developing new software applications, providing thoughtful analytical support for the planning process, and improving service through thoughtful data-driven evaluation.

OSPE partnered with the University of Toronto and Mitacs to create a detailed study on the current state of DRT systems in Canada. To read the full research report, visit ospe.on.ca/advocacy/our-work/research-reports/.

*Mitacs is a not-for-profit organization that has designed and delivered research and training programs in Canada for 20 years. Working with 60 universities, 4000 companies, and both federal and provincial governments, they build partnerships that support industrial and social innovation in Canada.

This article is republished from The Voice Magazine of the Ontario Society of Professional Engineers, Fall 2020 issue, pp. 31-32, with permission. Read the original article.

Willem Klumpenhouwer is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Transit Analytics Lab, where he works on bus and rail reliability, emerging technologies, and transit advocacy through data analytics.

Related content

- “The State of Demand-Responsive Transit in Canada,” by Dr. Willem Klumpenhouwer, Final Report, July 2020.

- Flexibility in a pandemic: Best practises for demand-responsive transit in Canada